The trip started with cigars.

The night before we launched on our 2,061-mile trip, my sister Carol and I sat out by her pool in the moist dark with crisp glasses of white wine. We each sparked up a skinny, cherry-flavored cigar with a filtered end. A girlie smoke. As a general rule, neither of us smokes. But it seemed that we needed something a little bold, a little silly, to bond over before we climbed into the car for the long, long trip. Carol’s kept going out. I, on the other hand, had no problem rhythmically puffing streams of smoke out over the glassy still water in front of us. We talked about many things; husbands, kids, grandchildren, our work, even my little dog. I began to worry if we covered all those topics now, there would be little left to keep us going on a trip that would span roughly 40 hours. I shouldn’t have bothered.

I intended to blog as we traveled, posting an update when we reached each day’s destination and I did manage a short, rather dull post the first night. But after that it didn’t get done. In fact, several of our expectations were unrealized. The little bottles of wine we stashed in a small cooler went unopened, the remaining cigars unsmoked.

Here’s the thing about spending hours on end in a car. Even when the forward motion mercifully stops, every nerve in your body keeps going. There is a ghostly sensation of the rumbling road, your ears continue to strain for the humming of the engine, and your brain … well, your brain impulses seem to be struggling through a thick bowl of guacamole. Every thought, every word you endeavor to speak, is a slow go. So, we tended to just flop into bed, feeling fortunate if our synapses coordinated enough to allow for face washing and teeth brushing.

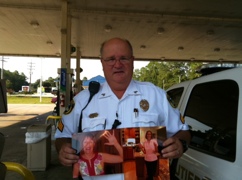

That’s not to say we didn’t enjoy ourselves. As Carol noted on our way out of Jacksonville, “We may have to make our own fun.” That’s where sisters Mary and Donna came in. In the tradition of Flat Stanley, we carried a picture of each of them. Posing them became one our chief amusements. They appeared on every “Welcome to …” sign we found as we entered each of the seven states. They were propped up amongst bottles of locally brewed beer. They were posed with two separate police officers and a couple of friendly bikers. For all our time in Texas (and believe me, we spent a lo-o-ng time in Texas) a picture of Rick Perry was taped to Donna’s shoulder. When we left the state we took a picture of the crumpled Rick and posted it to the family, announcing he was “crushed” to be left behind. We taped our sisters up in a sheriff’s office window like wanted posters, and hung them on cacti. They were photographed on the bank of the Rio Grande and on an ordinary bus bench. As we shared the photos by email, family members joined in, spinning tales of their naughty behavior or protesting their innocence, even as they marked the progress of the trip. As long as the pictures kept coming, they knew we were just fine.

You can see some of the flat sisters pictures at the end of this post.

We bought funky Western shirts in New Mexico and microbrew and po’ boys in Louisiana. We ate boudin sausages with cracklin’ as we streaked down the interstate. In San Antonio, where we spent a day off the road with Carol’s college roommate, we lounged by the pool, were treated to much-needed massages and talked religious philosophies (with a dash of politics) into the night.

It was a ghastly hot summer all over the country, but with the drought poor Texas is nearly burned up. In San Antonio our friend drove us around the end of an extinguished wild fire, the acrid, smoky smell still permeating into the car. Foraging deer with their fawns were out in the middle of the day, starving and looking for water. Even the humans couldn’t not feel it. The air seemed to suck any moisture right out of our skin. Lip chap was indispensable and we swilled bottles of water as we traveled.

Everyone warned us about the drive through West Texas, but even though we were prepared, the sand and mesquite was so vast, so seemingly endless, that we had the sensation of running in place, the engine grinding monotonously but the view never changing. Both of us had a shocking moment behind the wheel to find the speedometer hovering at 100. And still it felt we were getting nowhere. Any break in the monotonous landscape was cause for comment, and we had an entire conversion about an ordinary freight train we could see miles in the distance. When we finally met it we spotted a small grass fire that must have been kicked up by a spark from its wheels. I called 911 and the dispatcher seemed grateful for the heads-up, saying they’d send someone right out.

A small rainstorm did come up that day, dropping the temperature to a merciful 65. Less than 20 miles later, the sun was out again and the car’s outside thermometer was pushing 90. Yes, it is a land of extremes.

At one point we had to drive 13 miles off the interstate to find gas. You’d think that would have made a lasting impression on us, but somehow when we left El Paso both of us flat-out forgot that the tank was low again. Somewhere in the New Mexico badlands Carol was behind the wheel and gasped, “My God, we’re out of gas!” She had no idea how long the low fuel light had been on and the needle was on empty. The next 15 miles were mighty quiet. Happily a gas station hove into view in the nick of time. They commanded a premium price for their gas, but we felt lucky to get it. We figured there was only 2/10ths of a gallon left in the tank.

At a temporary border patrol stop, we fished in our bags for our IDs, both profoundly uncomfortable first at having to “show” our papers, and secondly when we were waved on through with barely a glance, presumably because middle-aged, very white women didn’t fit the profile. We talked about that through many of the following miles.

When we finally rolled into Scottsdale, five days from when we started, we looked at each other in wonder, as if the city had snuck up on us. It felt like we’d gone down Alice’s rabbit hole and come out the other side. For a split second after Carol killed the engine we were silent. And then I said, “We did it.” And she sighed, “We sure did.”

That night, on the patio of her temporary home, we lit cigars and looked out on another, very different pool. Were there any new insights gained? Any wisdom about our country or the people in it? All I can say is that everyone likes to have fun. A surprising number of people joined into the game with our flat sisters. At the James Avery Jewelry showroom we visited, nearly the whole staff laughed over hanging pieces all over sister Mary’s picture. And, to my surprise, off-duty cops have a better sense of humor than I would have guessed.

For me, the meaning of the trip lay in reconnecting with my sister. We’ve always shared the bond of growing up in the same house, with common parents and siblings. But we’ve been adults for a very long time, with different homes, spouses, children and experiences. For five days, we shared a one-on-one experience, arguing a little, laughing a lot and making memories that are special and unique to only us. Bottom line, it was fun. My sister and I spent time together and it was fun.

And we both like the occasional girlie cigar.